A few weeks back in one of our Friday morning art group meetings we asked the participants, a group of refugee women from the DRC and Burundi to list in order of significance the challenges they faced in Johannesburg right now. Without stopping to think Marie stated: “paper; job; health; accommodation”. The others all agreed. Every week the discussions held amongst the group as they sit and work on their quilt pieces relay the daily challenges and, traumas of living as non-national migrants in South Africa. In our group all of the women are refugees but only one has refugee status. The rest are on Asylum Permits, which have to be renewed regularly and which subject them to multiple vulnerabilities in the city.

After listing their challenges the women described the difficulties of dealing with documentation – of the long hours spent in queues at home affairs; of the disregard and abuse from security guards and officials managing the queues and, of the corruption of home affairs employers taking bribes to ensure that you can a foot inside the building and have a hope of getting your papers renewed. The process of renewal is challenging and often, demoralising. Regularly the women wait for hours outside the Home Affairs building in Pretoria only to be told they are too far back in the queue, that it is not the day for migrants from the DRC, or that there is some other arbitrary reason why they can’t be helped. Aside from the travel costs to Pretoria, the day spent in a queue and, the money spent on childcare, the frustration and exhaustion of repeatedly trying to be seen is tough. The women are always trying to be recognised as more than a body in a queue, of being distinguishable from the hundreds of others, all of whom have their own stories and demands to be heard. Home Affairs is hard work for everyone – but when your existence in a country, your right to work, your access to healthcare and accommodation and your safety depend on it – it’s a different matter.

After listing their challenges the women described the difficulties of dealing with documentation – of the long hours spent in queues at home affairs; of the disregard and abuse from security guards and officials managing the queues and, of the corruption of home affairs employers taking bribes to ensure that you can a foot inside the building and have a hope of getting your papers renewed. The process of renewal is challenging and often, demoralising. Regularly the women wait for hours outside the Home Affairs building in Pretoria only to be told they are too far back in the queue, that it is not the day for migrants from the DRC, or that there is some other arbitrary reason why they can’t be helped. Aside from the travel costs to Pretoria, the day spent in a queue and, the money spent on childcare, the frustration and exhaustion of repeatedly trying to be seen is tough. The women are always trying to be recognised as more than a body in a queue, of being distinguishable from the hundreds of others, all of whom have their own stories and demands to be heard. Home Affairs is hard work for everyone – but when your existence in a country, your right to work, your access to healthcare and accommodation and your safety depend on it – it’s a different matter.

More recently the women have been returning from Home Affairs having failed to renew their permits. One week Patience went three times but on each visit she found the queue was too long. When Mary went an official looked at her paper (she has appealed the rejection of her refugee application), told her to wait to one side and then, when realising her husband was not with her (the appeal paper stated the appeal was conditional on her being accompanied by her husband) shouted at her to go home. He did not allow Mary to explain that her husband has been missing for many months now and that she does not know where he is. She has been coping alone with three children and without work, a permanent place to stay and in a state of severe trauma for a long time. This did not matter to the official. Nor did it matter that the country from which Mary has fled remains volatile, violent and a place that she cannot return to. Mary – like the others can’t go home – yet she can’t stay easily or peacefully in South Africa either. Her temporary and precarious documentation renders her an ‘outsider’ and ‘undesirable’– and despite legally being allowed to work and access healthcare with an asylum permit – she struggles with both.

A few weeks back Rachel was mugged. She had been helped to find some money to pay for a seat in a hair salon where she could earn money by doing clients hair. This is something she is trained in and her skills are well-known. The R2000 she had on her, her phone and her asylum papers were taken by a group of men who stopped their car, beat her up and drove off with her bag. In retelling this traumatic experience Rachel had noted, “Even though I couldn’t walk, everything was hurting…the next day I went back there to the place it happened. I checked for my bag in the bins and all over. I didn’t find it but I found my papers (asylum papers)…that was so lucky. If I lost those papers….”

Rachel’s comments highlight the importance and significance of papers – and what their physical presence represents. Rachel had been badly beaten and then refused help by the clinic and also by the police when she went to report the case. But this was less important than the fact that her papers had been taken. While the bruises and the trauma of this incident will take a while to heal, finding her papers has restored a tiny piece of hope. Despite the papers being constantly contested and discredited for Rachel they are her way of affirming her rights in the city, they are a form of communication with those who challenge her existence, and within the crumpled white sheets and black ink they hold together her story – of how she came to be here and where she wants to go.

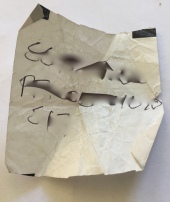

Mercy has a small scrap of paper – in fact it is the back of a ripped receipt upon which a series of numbers have been written. That’s her documentation. She carries it around in her purse. Last week the police stopped her and her friends on the street and asked to see their papers. Mercy ran away. She tells me that the last time she went to home affairs the woman she spoke to told her that in exchange for a “cool drink” she could “fix her papers”, meaning this scrap of paper could be converted to an actual asylum permit. “How much is the cool drink?” I ask her – knowing that it is not a R10 can of coke. “R500” (approx. £30) she replies. “I didn’t have it last time…so I go again next week. I’ll sleep in the church then I can be at the front of the queue”. I ask her where she will get R500 since she is currently living in a shelter and not working. “I don’t know” she replied “but I will go.”

Mercy has a small scrap of paper – in fact it is the back of a ripped receipt upon which a series of numbers have been written. That’s her documentation. She carries it around in her purse. Last week the police stopped her and her friends on the street and asked to see their papers. Mercy ran away. She tells me that the last time she went to home affairs the woman she spoke to told her that in exchange for a “cool drink” she could “fix her papers”, meaning this scrap of paper could be converted to an actual asylum permit. “How much is the cool drink?” I ask her – knowing that it is not a R10 can of coke. “R500” (approx. £30) she replies. “I didn’t have it last time…so I go again next week. I’ll sleep in the church then I can be at the front of the queue”. I ask her where she will get R500 since she is currently living in a shelter and not working. “I don’t know” she replied “but I will go.”

Mercy’s scrap of paper, Mary’s appeal papers and Rachel’s lost and found papers are simultaneously useless and vital. They are useless because none of the women can get work while on an asylum permit; they are denied access to healthcare and they are always treated as an “other” in their everyday lives. But without these papers they are lost – the shadowy lives they are already forced to lead become even fainter. As Mary stated “I am not a person…this small piece of paper…this is what I am”.

Having the right papers and documentation does not solve everything. It doesn’t ensure you can find a job, can rent a room or that you will be able to access healthcare. It doesn’t topple the intersecting and compounding layers of risk and vulnerability – nor take away previous traumas suffered and current experiences of loss. But it can offer a little sense of security, of legitimacy, of rights – and some confidence to exist in the spaces you occupy. Sometimes surviving the city, making every day work and being able to come up for air can depend on that. As Mary stated, when waving her asylum paper in front of me “if I can just fix this…this small, small thing…then it can be better.”

Poking the wound – research, stories and process – thinking through the complexities